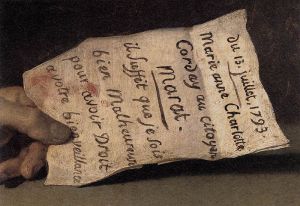

In July 1793, an unknown 24-year-old woman called Charlotte Corday arrived in Paris from Caen, in Normandy. She found herself lodgings, bought a bread knife, and went to the National Assembly in search of Jean-Paul Marat, a journalist, and one of the extremists within the Jacobin party. He wasn’t there, so she wrote him a letter, asking if she could visit him. She was turned away from his home in the morning, but later in the day he agreed to a meeting, and she turned up – with a knife.

Charlotte Corday was well educated in a convent in Caen where she was exposed to the new ideas of the enlightenment, but she was appalled by the violence of the revolution, the execution of Louis XVI, and the possibility of civil war. Today she is best known for a painting in which she doesn’t even appear, except for her signature on a piece of paper.

The Death of Marat is now one of the most famous images of the French Revolution, though it was not always so. It is an amazing painting, not least because the bizarre setting, with Marat sitting in his bath to receive a woman visitor. The other point that, to me, makes the story remarkable, is the letter. For a start, it still exists, complete with bloodstains, in a collection of French Revolutionary memorabilia owned by a Scottish aristocrat.

Even more remarkably, it shows that Paris, in the middle of the most violent phase of a violent revolution, still had a functioning postal system. We often forget the ordinary, in the midst of extraordinary events. But the post must get through.

Communication plays an important part in any revolution, and the gradual changes in communications technology have played an important role in changing the way revolutions occur – just as they have changed lives in general.

Recently, there has been a lot of chatter about the impact of new media – the Internet, Facebook, Twitter and the rest – on events across the Middle East and North Africa. There seems no doubt that they have been important, just as Al Jazeera provides a new source of information, delivered in an established way, TV.

Communication is essential in any rebellion, to rally the troops (literally or metaphorically) and to maintain the flow of information. In 1986, a ‘peoples’ power’ revolution in the Philippines overthrew President Marcos. During the days of popular demonstrations in Manila, people used mobile (cell) phones for the first time to direct crowds from place to place. And that successful revolution was in many ways a model for the successful revolutions in Eastern Europe during 1989.

Sometimes communications fail, and in the absence of reliable information, rumours fester. During the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, the rebels seized the General Post Office (where else?) north of the river, but the British forces held the bridges across the Liffey, as well as Trinity College, in central Dublin. I had an Irish friend whose family lived south of the river. His mother remembered how isolated they felt and how little they knew of what was going on across the river.

Between them, the rebels and government forces disabled the post, telegrams and phones in Dublin, but a city is too large and complex an organism to survive for long without effective communication. And nowadays we are all so dependent on the Internet that we can’t do without it. Stop Twitter, Facebook and the rest – as some Middle Eastern governments have tried to do – and you also stop credit card transactions and synchronised traffic lights.

So the show must go on. My husband happened to be travelling in Greece in 1974, when the military junta was overthrown and the monarchy abolished. When he went to a Post Office to send off postcards, the stamps he bought were old ones, printed by the overthrown regime, but each stamp was carefully defaced, the King’s head smeared with a blob of ink. A little ideological modification – but the post gets through.

New media played a role in the Protestant Reformation too. In 1517, Martin Luther, a monk and an academic at the local university, nailed 95 Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, criticising various practices of the Catholic Church. The ‘theses’ were academic debating points, and Luther anticipated an academic debate. He wasn’t the first scholar to criticize the Church, but what made things different from earlier reformers was Gutenberg’s invention of moveable type. (Or rather, reinvention; the Chinese got there independently much earlier.)

Faster communication was key. Once Luther’s original words were printed and distributed, the criticisms of the established order spread faster than ever before possible: within a week they were all over Germany, within a month all over Europe. Once out there, these ideas generated other ideas, which multiplied and fragmented and took on new and different forms – and generated equally proliferating reactions as well.

In 16th century terms, printing allowed ideas to spread faster than ever – across Europe in a month! In the 18th century, the ideas of the French Revolution crossed Europe within days, along established postal routes or by carrier pigeon. Today ideas can spread as fast as your local broadband connection can manage.

But we still face the same problem of separating ideas from rumours, and dealing with the proliferation and fragmentation of ideas. We can certainly communicate faster than ever before. But I suspect we still process that information at much the same speed as we did 500 years ago. And too often, the simplest solution to dealing with the speed of change is to buy a breadknife.

Highly recommended: ‘Live-Tweeting the 1986 People Power Revolution’